We live and think not in isolation, Arendt argues, but in an interconnected web of social and cultural relations - a framework of shared languages, behaviors, and conventions that we are conditioned by every single day. This idea is best understood within the context of how Arendt viewed our relationship to the world. Ordinary people - going about their everyday lives - become complicit actors in systems that perpetuate evil. Evil becomes commonplace it becomes the everyday. Rather, evil is perpetuated when immoral principles become normalized over time by unthinking people.

The “banality of evil” is the idea that evil does not have the Satan-like, villainous appearance we might typically associate it with. He carried out his murderous role with calm efficiency not due to an abhorrent, warped mindset, but because he’d absorbed the principles of the Nazi regime so unquestionably, he simply wanted to further his career and climb its ladders of power.Įichmann embodied “the dilemma between the unspeakable horror of the deeds and the undeniable ludicrousness of the man who perpetrated them.” His actions were defined not so much by thought, but by the absence of thought - convincing Arendt of the “banality of evil.” Evil is not monstrous it takes place under the guise of 'normality' In her report for The New Yorker, and later published in her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Arendt expressed how disturbed she was by Eichmann - but for reasons that might not be expected.įar from the monster she thought he’d be, Eichmann was instead a rather bland, “terrifyingly normal” bureaucrat. Indeed, Arendt was a German philosopher and political theorist who saw the techniques and evil consequences of totalitarian regimes firsthand.īorn into a secular-Jewish family, Arendt fled Nazi Germany in the 1930s, eventually settling in New York, where after the war she covered the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.

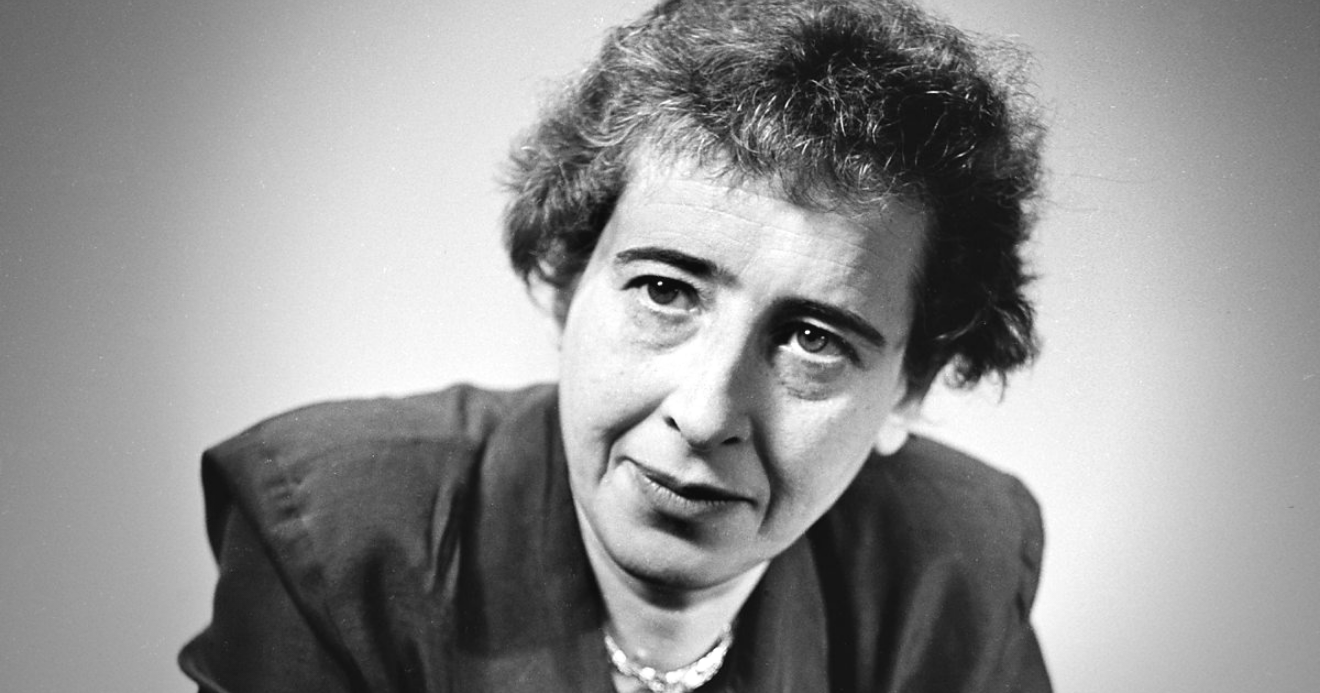

Where does evil come from? Are evil acts always committed by evil people? Whose responsibility is it to identify and stamp out evil? These questions concerned 20th-century German philosopher Hannah Arendt throughout her life and work, and in her final (and unfinished) 1977 book The Life of the Mind, she seems to offer a conclusion, writing:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)